January is always a good time for a faculty retreat, particularly in Tempe Arizona. This week I have the privilege of attending the Oikonomia Network Faculty Retreat. It is a time to see a little of the city but also to network with other faculty and innovators interested in advancing theological education in faith, work, and economics. The Oikonomia

January is always a good time for a faculty retreat, particularly in Tempe Arizona. This week I have the privilege of attending the Oikonomia Network Faculty Retreat. It is a time to see a little of the city but also to network with other faculty and innovators interested in advancing theological education in faith, work, and economics. The Oikonomia  Network gathering is sponsored by the Faith, Work and Economics initiative at

Network gathering is sponsored by the Faith, Work and Economics initiative at ![]() the Kern Family Foundation. The Network represents a group of scholars and educators engaged in seminary education around the United States, all working on projects to prepare seminarians to take seriously the place of work and economics as part of their ministry.

the Kern Family Foundation. The Network represents a group of scholars and educators engaged in seminary education around the United States, all working on projects to prepare seminarians to take seriously the place of work and economics as part of their ministry.

Greg Forster, Director, Oikonomia Network and Visiting Assistant Professor of Faith and Culture at Trinity International University, convened this evening’s gathering by noting the title of the retreat “Strategies for Hope.” Forster offered that, in the middle of unsettled

Greg Forster, Director, Oikonomia Network and Visiting Assistant Professor of Faith and Culture at Trinity International University, convened this evening’s gathering by noting the title of the retreat “Strategies for Hope.” Forster offered that, in the middle of unsettled  times, we need to recognize there are a number of encouraging activities occurring so members need fresh, hopeful, eyes to discern those positive efforts and build on their initiatives. Forster also acknowledged

times, we need to recognize there are a number of encouraging activities occurring so members need fresh, hopeful, eyes to discern those positive efforts and build on their initiatives. Forster also acknowledged  that the retreat followed a new, abbreviated, format. In part, the change of the retreat is directly related to a new Oikonomia initiative called the Karam Forum that occurs

that the retreat followed a new, abbreviated, format. In part, the change of the retreat is directly related to a new Oikonomia initiative called the Karam Forum that occurs  March 2-3, 2017 at Trinity International University. Still, the retreat remains an important event as it both helps new members gain an initial understanding of the network’s efforts, and also allows experienced Oikonomia Network faculty and administrators ongoing opportunity to build their expertise and look for “the next step” to constructively expand their efforts.

March 2-3, 2017 at Trinity International University. Still, the retreat remains an important event as it both helps new members gain an initial understanding of the network’s efforts, and also allows experienced Oikonomia Network faculty and administrators ongoing opportunity to build their expertise and look for “the next step” to constructively expand their efforts.

Daniel Aleshire, executive director, Association of Theological Schools (ATS), served as the keynote speaker this evening on the theme “The Future of Theological Education.” Alshire focused primarily on the state of Evangelical Seminaries in the USA and Canada. Aleshire observed that the term “Evangelical” can be a fluid term, often subject to definition. However, normally the term includes self-identified Evangelical seminaries, as well as other seminaries with core confessional statements that closely resemble the same evangelical qualities. Overall, with approximately 270 seminaries in the ATS, roughly 110 seminaries would be identified within the Evangelical/Protestant camp, another approximate 100 coming from Mainline/Protestant traditions, and the remainder serving other Christian traditions such as Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox seminaries.

Daniel Aleshire, executive director, Association of Theological Schools (ATS), served as the keynote speaker this evening on the theme “The Future of Theological Education.” Alshire focused primarily on the state of Evangelical Seminaries in the USA and Canada. Aleshire observed that the term “Evangelical” can be a fluid term, often subject to definition. However, normally the term includes self-identified Evangelical seminaries, as well as other seminaries with core confessional statements that closely resemble the same evangelical qualities. Overall, with approximately 270 seminaries in the ATS, roughly 110 seminaries would be identified within the Evangelical/Protestant camp, another approximate 100 coming from Mainline/Protestant traditions, and the remainder serving other Christian traditions such as Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox seminaries.

Dan opened his presentation observing how deeply Evangelicals seminaries are shaped by a shared context. Aleshire noted that a number of the seminaries began after the rise of North American Evangelicalism, as a movement, in the 1960s and 1970s. So Evangelical seminaries, who prove quite “young” by comparison, remain as vibrant as their constituent

Dan opened his presentation observing how deeply Evangelicals seminaries are shaped by a shared context. Aleshire noted that a number of the seminaries began after the rise of North American Evangelicalism, as a movement, in the 1960s and 1970s. So Evangelical seminaries, who prove quite “young” by comparison, remain as vibrant as their constituent  church base that also emerged within the last fifty years. So, as the Evangelical movement goes, so goes the seminaries founded in its expansion. The success or decline of those seminaries remains closely aligned to the communities that founded them. Also, Evangelical seminaries have appeared the most creative and innovative seminaries in pioneering extension and distance education, creating new degree programs and experimenting with current MDiv programs. Aleshire noted that most seminaries act more like basketball players than ballerinas. Dan said that seminaries often have a “pivot foot” that stays anchored to the ground (where ballerinas jump with both feet), and often the “pivot” rests either with a grounded theological confession, or a grounded understanding of traditional educational practice. Since most Evangelical seminaries focused on a common creedal or confessional heritage they were freer to experiment in educational efforts. By contrast, Mainline Protestant seminaries might be more theologically diverse but very fixed on a particular pattern of educational understanding. Regardless, the relative need to stay close to its constituency, and need to innovate, define the context of Evangelical seminaries.

church base that also emerged within the last fifty years. So, as the Evangelical movement goes, so goes the seminaries founded in its expansion. The success or decline of those seminaries remains closely aligned to the communities that founded them. Also, Evangelical seminaries have appeared the most creative and innovative seminaries in pioneering extension and distance education, creating new degree programs and experimenting with current MDiv programs. Aleshire noted that most seminaries act more like basketball players than ballerinas. Dan said that seminaries often have a “pivot foot” that stays anchored to the ground (where ballerinas jump with both feet), and often the “pivot” rests either with a grounded theological confession, or a grounded understanding of traditional educational practice. Since most Evangelical seminaries focused on a common creedal or confessional heritage they were freer to experiment in educational efforts. By contrast, Mainline Protestant seminaries might be more theologically diverse but very fixed on a particular pattern of educational understanding. Regardless, the relative need to stay close to its constituency, and need to innovate, define the context of Evangelical seminaries.

Out of that context, Aleshire offered four major factors that may shape the future of Evangelical Seminaries. The first revolved around changes in enrollment. All seminary enrollment has declined and, while Evangelical seminaries have more students than Mainline seminaries, they often “feel” the drop of enrollment more. In particular, Aleshire noted that North American Evangelicalism has plateaued and now is in modest decline. A decline in the constituency may present problems for future enrollment and also affect the culture of seminaries serving what appears to be a plateaued movement in the USA.

Out of that context, Aleshire offered four major factors that may shape the future of Evangelical Seminaries. The first revolved around changes in enrollment. All seminary enrollment has declined and, while Evangelical seminaries have more students than Mainline seminaries, they often “feel” the drop of enrollment more. In particular, Aleshire noted that North American Evangelicalism has plateaued and now is in modest decline. A decline in the constituency may present problems for future enrollment and also affect the culture of seminaries serving what appears to be a plateaued movement in the USA.

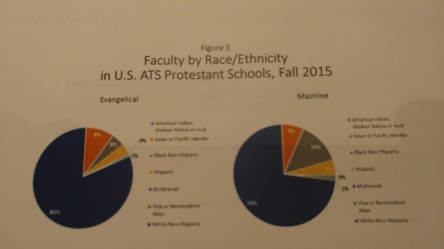

Second, the ethnic composition of the USA and Canada is changing. In the next forty years, more people of color will determine the demographics of these countries than white Americans, and they will probably constitute some of the more vital Christian congregations as well. Currently Protestant theological schools (Evangelical and Mainline) experience about 41% of their student body from other ethnicities. Evangelical seminaries see the diversity  more equally separated in Hispanic, Black, and Asian constituents, while Mainline seminaries attract more black Christians. Yet 82% of Evangelical Seminary faculty remain “white” (compared to 73% white in the Mainline). Aleshire notes the inevitable change to a diverse world means that pastors being educated today will guide congregations who live in a much more diverse world.

more equally separated in Hispanic, Black, and Asian constituents, while Mainline seminaries attract more black Christians. Yet 82% of Evangelical Seminary faculty remain “white” (compared to 73% white in the Mainline). Aleshire notes the inevitable change to a diverse world means that pastors being educated today will guide congregations who live in a much more diverse world.

Third, Evangelical seminaries face a challenge in restructuring revenue streams in the future. Aleshire observed that Evangelical seminaries rely more heavily on tuition, independent gifts, and denominational resource (which shrinks as denominations change). What they lack is a kind of balance funding base (including endowments) so they are particularly vulnerable to the immediate financial

Third, Evangelical seminaries face a challenge in restructuring revenue streams in the future. Aleshire observed that Evangelical seminaries rely more heavily on tuition, independent gifts, and denominational resource (which shrinks as denominations change). What they lack is a kind of balance funding base (including endowments) so they are particularly vulnerable to the immediate financial  climate in the United States. As the general economy goes, so goes the financial life of Evangelical seminaries, which leaves them susceptible during poor economic periods (with no endowment to buffer). Aleshire was quick to admit that seminary students have “maxed out what they can pay,” so cannot afford additional debt to support seminary shortfalls. This means that Evangelical seminaries face a challenging financial future under current revenue strategies.

climate in the United States. As the general economy goes, so goes the financial life of Evangelical seminaries, which leaves them susceptible during poor economic periods (with no endowment to buffer). Aleshire was quick to admit that seminary students have “maxed out what they can pay,” so cannot afford additional debt to support seminary shortfalls. This means that Evangelical seminaries face a challenging financial future under current revenue strategies.

Fourth and finally, Aleshire noted that the future of Christianity lies in global expansion in the “majority world” rather than on USA/Canada soil. The rapid rise of a “Global South” Christianity provides a clear indicator that theological education must partner with other global efforts and schools. Aleshire noted that Evangelical seminaries seem to be doing better in this initiative, creating stronger connections and more frequent partnerships.

Fourth and finally, Aleshire noted that the future of Christianity lies in global expansion in the “majority world” rather than on USA/Canada soil. The rapid rise of a “Global South” Christianity provides a clear indicator that theological education must partner with other global efforts and schools. Aleshire noted that Evangelical seminaries seem to be doing better in this initiative, creating stronger connections and more frequent partnerships.

Aleshire summarized that in the four factors, Evangelical seminaries seem to be doing well in some, and remain vulnerable to others. Recognizing that these indicators might not fully describe the future, they may stimulate change. Yet Aleshire also noted that there may be unforeseen forces that stimulate change as well. Often change does not occur when everything is going well. For instance, Aleshire remarked that none of the Mainline Protestant seminaries were worried about innovation in 1959, and could not have foretold then of the rise of the Evangelical movement that shaped USA Christianity for the rest of the 20th century. In similar fashion, Evangelicalism and its constituent seminaries may just now be feeling discomfort but really do not know what other social factors may challenge theological education going forward.

Moving to a speculative, yet cautious, perspective Aleshire offered that the need to engage “diversity” both when it comes to ethnic and international changes in student population, but also when engaging educational innovations that prove important. Aleshire noted that not all educational “experiments” will prove successful, but a willingness to adapt to change will prove important. Aleshire also surmised that schools will be most successful in the future as they cultivate a faithful constituency of individuals and congregations to provide the needed funding, students and places of service. This means that denominational seminaries will have to focus more at the congregational level, developing a network of communities to support their efforts.

Finally, Aleshire believes that the paradigm of theological education will shift from the professional school model to the “formational” model. This almost inevitable secularization of culture will mandate that seminaries cannot assume their students possess a strong discipleship background even while expressing and exploring a call to ministry. Instead, Seminaries will have to accept the responsibility of shaping Christian character as well as provide professional training. Aleshire observed that there have only been two predominant approaches to clergy education in the history of the United States. Early the focus at schools like Harvard and Yale entailed providing a “classical” curriculum that shaped a “learned” minister. By the 1800s a shift occurred (much like law and medicine) from the liberal arts college to the professional school. And, while Evangelical constituents might not always be happy with this approach, this model of clergy education is the only dominant model Evangelical Seminaries knew. Which the shift toward

Finally, Aleshire believes that the paradigm of theological education will shift from the professional school model to the “formational” model. This almost inevitable secularization of culture will mandate that seminaries cannot assume their students possess a strong discipleship background even while expressing and exploring a call to ministry. Instead, Seminaries will have to accept the responsibility of shaping Christian character as well as provide professional training. Aleshire observed that there have only been two predominant approaches to clergy education in the history of the United States. Early the focus at schools like Harvard and Yale entailed providing a “classical” curriculum that shaped a “learned” minister. By the 1800s a shift occurred (much like law and medicine) from the liberal arts college to the professional school. And, while Evangelical constituents might not always be happy with this approach, this model of clergy education is the only dominant model Evangelical Seminaries knew. Which the shift toward  “formation,” seminaries will be tasked with “making Christians” more than providing professionals. Of course, the challenge may entail not only a shift in the curriculum but a need for a longer, sustained, relationship between seminary and pastor well before and well past the completion of any “degree.” Still, Aleshire believes classrooms will move from less emphasis on critical engagement and technical knowledge to a more general guidance toward Christian maturity.

“formation,” seminaries will be tasked with “making Christians” more than providing professionals. Of course, the challenge may entail not only a shift in the curriculum but a need for a longer, sustained, relationship between seminary and pastor well before and well past the completion of any “degree.” Still, Aleshire believes classrooms will move from less emphasis on critical engagement and technical knowledge to a more general guidance toward Christian maturity.

Ultimately congregations seem to expect pastors to answer three questions

- Do you love God?

- Do you love me?

- Can you do the work?

Aleshire admitted that the ordering of these questions prove crucial and most congregants really will tolerate a limited ability to do the work as long as they know the pastor authentically loves God and them. However, it never reverses in order of expectation.

Overall Aleshire provided both challenges and invitations to seek “hopeful” signs for the future. The reflection and discussion following this opening event should prove fruitful.